A Giving Heart: One Couple’s Push for Visibility amidst a Fight against Frontotemporal Degeneration

By: Ananya Chandhok

Photography Provided By: Amy Bouschart

In September 2024, Amy Bouschart—former coach, public speaker, and neurotech sales representative—flew from Arizona at a moment’s notice.

Across the country, back in Chicago, was a piece of paper that she had had only dreamed of receiving — a citywide proclamation from Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson officially recognizing frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) Awareness Week (September 22-29, 2024).

Jitters and excitement churned inside her, as she made her way into the city. This was a day she had been waiting years for. She had waited for this day for years. And while the pouring rain and the city’s congested traffic made one final push to slow her down from her destination, she pushed onward to her destination: Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office.

Amy zipped up the elevators and was delivered face-to-face with the paper she’d come all this way for. Her tumultuous journey finally being met with swiftness confirmed her belief in the cause that brought her here in the first place.

After all, it was all for the love of her life — her husband Frank Callea, a former VP of Media Technology at the Chicago Tribune. It was to recognize his and countless others’ fights against FTD — a type of dementia syndrome with variants that can result in difficulties with language, motor function, cognitive ability and behavior, according to the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease.

Amy Bouschart spoke to the Center about the couple’s journey for a Chicago proclamation recognizing FTD Awareness Week, as they work towards their next step: a resolution recognizing the disease across Illinois.

Amy Bouschart, 62, FTD advocate, and her husband Frank Callea, 62, were presented with an official proclamation recognizing FTD Awareness Week in the City of Chicago; the couple is pictured at their wedding in 2011.

A Lifetime of Community Service

The Bouscharts lived in Chicago for their entire lives, so giving back to the community was a natural next step for them.

“Frank was the one that reached out first and contacted Northwestern Medicine about volunteering,” Amy said. “Then we decided to do this together.”

One of Amy's core memories was when they worked on a TV bingo show for patients at the hospital.

“It sounds so silly and so fluff and everything,” she said. “But our ability to get on camera and do a bingo show, lift people’s spirits, go into their rooms to deliver a prize, and hopefully leave the people a little better off and feeling a bit more cared for was important.”

Frank was well on his way towards the 25-year-mark for volunteering at Northwestern when his health began to deteriorate in 2016. Soon, Frank found himself back to the hospital, but this time as a patient.

“It was very odd walking into the hospital that day,” Amy said. “We had walked in for many years volunteering and then to walk in that day when we knew something wasn’t right.”

Amy felt the changes in Frank, even before getting an official FTD diagnosis.

“I still remember putting my hand in his hand and walking into the hospital…I remember thinking and asking myself a question, 'what was this going to mean?'”

Even though Amy saw parts of Frank’s personality shift, his giving heart never did. The couple stuck to volunteering, hoping to keep a sense of normalcy and routine.

“I remember when Frank wasn’t understanding things after his diagnosis,” Amy said. “He wasn’t making sense on the [bingo] camera, but he still wanted to train new volunteers.”

Even as his disease progressed, Amy and Frank found some comfort and humor through it all.

“When Frank was younger, he always wanted to be like the athlete Ted Williams, who wanted to freeze his head,” Amy said.

So when a team of researchers from the Mesulam Center approached the couple about brain donation and research participation, their inside joke found its way through the cracks.

“I think they thought we were nuts,” Amy said. “It sounds ridiculous, but we were laughing. We had to find some light in this horrid, unfathomable journey.”

Giving back to the community was paramount for the couple, and research participation gave this autonomy back to them.

“I didn’t want him to lose that connection to doing something that he felt was really important, Amy said.”

And eight years into Frank’s FTD diagnosis, Amy knew it was time to use her connection to raise awareness for FTD.

“It’s time to help,” she said.

Amy Bouschart and her husband Frank Callea live a life of advocacy, after Frank was diagnosed with FTD in 2016; the couple is pictured at a Northwestern Hospital volunteer event several years ago.

A Push for a Proclamation

Amy felt disconnected at times, unable to find spouses who were experiencing the same emotions and changes as her.

“I either found people that were in their 70s or a little older,” Amy said. “I kept thinking 'but you had the choice of retirement…We didn’t get that.'”

Eventually, their presence in the FTD space connected Amy to other spouses who faced the same loss of identity and choice.

“Stephanie Zimmerman…had lost her husband to FTD in a much shorter time than I did,” Amy said. “But she had reached out to me [a couple years prior] and said I think our stories are similar. [Both our husbands were diagnosed when they were 53 years old].”

“Boy, do I understand,” said Amy in her response to Zimmerman. “...I feel like we walk this disease so much by ourselves, and we don’t have the support that maybe people diagnosed with cancer have, [for example].”

This was the connection Amy was searching for.

And while it was a long, tumultuous road for the couple to find others like them, Amy knew that a proclamation held the power to connect others much earlier in their journeys and carry them beyond visibility.

She got to work on August 1, 2024, after meeting with the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD).

Amy worked double-time trying to get a proclamation pushed through Arizona and Chicago, in time for national FTD Awareness Week in September. The unanswered calls and emails were deafening and almost made Amy throw in the towel.

“We were a week away from the official FTD Awareness Week,” she said. “I was scrambling, reaching out to anybody and everybody.”

Chicago had to be the one, Amy said.

In the final hour of their efforts, her inbox lit up. The mayor’s office had awarded her with a proclamation announcing an official recognition of FTD Awareness Week in Chicago. That night, Amy shared the good news with Frank’s brother, one of her biggest supporters through their journey.

What followed felt like the biggest confirmation for Amy’s efforts.

“He said, ‘Guess who’s with me right now.’” said Amy remembering her conversation with Frank’s brother. “Frank was right there with him…I could hear him get all excited in the background.”

Hundreds of miles away, Frank and Amy were in sync with each other.

“He was making all these sounds of excitement,” Amy said. “It was almost like he knew. I felt like somewhere in there, he was there…my best friend, my husband.”

“Honey, we did good,” said Amy to Frank.

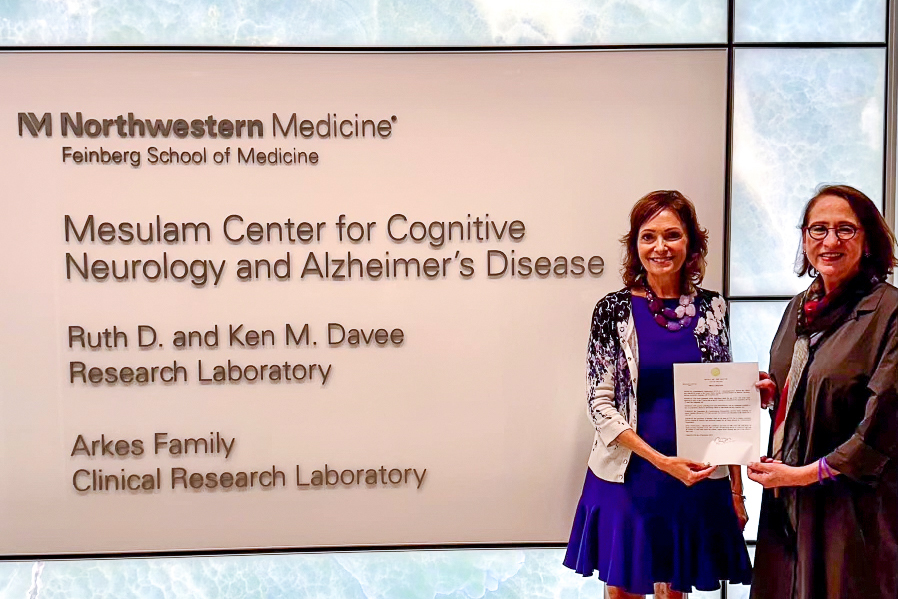

Amy Bouschart's first stop after receiving the official proclamation was the Mesulam Center. She is pictured with Darby Morhardt, PhD, LCSW, research professor and clinical social worker at the Mesulam Center.

Working for a State-Wide Resolution

Amy now hopes for legislative change to impact healthcare accessibility for people with FTD, especially those of whom have an early-onset diagnosis. She’s putting her weight behind securing a state-wide resolution, but for that to happen she needs local legislative support.

“The proclamation gave it [FTD] some more attention,” Amy said. “But it’s just the groundwork…The resolution is hopefully going to create a little bit more impact.”

Frank had a younger diagnosis, so he fell at the margins when qualifying for alternative care. He was denied care at three different locations because he was under 62.

When Amy did find a care center for Frank, the facility kicked Frank out after eight days. Eventually, they found a center that would support Frank, but the couple’s struggles are universal.

Legislative leg power for increasing visibility and accessibility to healthcare resources are long overdue for Frank and others.

“I’m in the middle of this journey, Amy said. “I’m not done.”