Researchers publish first-of-its-kind framework for standardizing dementia nomenclature

By: Ananya Chandhok

An “accidental advocate” is how Angela Taylor described herself, when it came to cognitive impairment disorders.

The vice president of strategic partnerships at the Lewy Body Dementia Association stumbled into her role through her father’s experience with dementia.

“When my dad got diagnosed…all we knew was that the doctor said he had mild cognitive impairment,” Taylor said. “When the doctor said it wasn’t Alzheimer's disease, we thought we dodged a bullet.”

However, Taylor’s father was diagnosed with the second most common form of progressive dementia: Lewy Body.

At every turn, she realized no one was familiar with the disease or understood what she was going through.

Taylor wasn’t alone in her struggle.

Stigma, naming inconsistencies, and a lack of education have historically compromised research and therapy development for dementia, according to the National Alzheimer's Project Act.

With a push to advocate, Taylor joined a team of like-minded researchers who formed the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative (DeNomI) — a nationwide plan to address limitations in communicating dementia diagnoses and increase the general public’s understanding of related diseases.

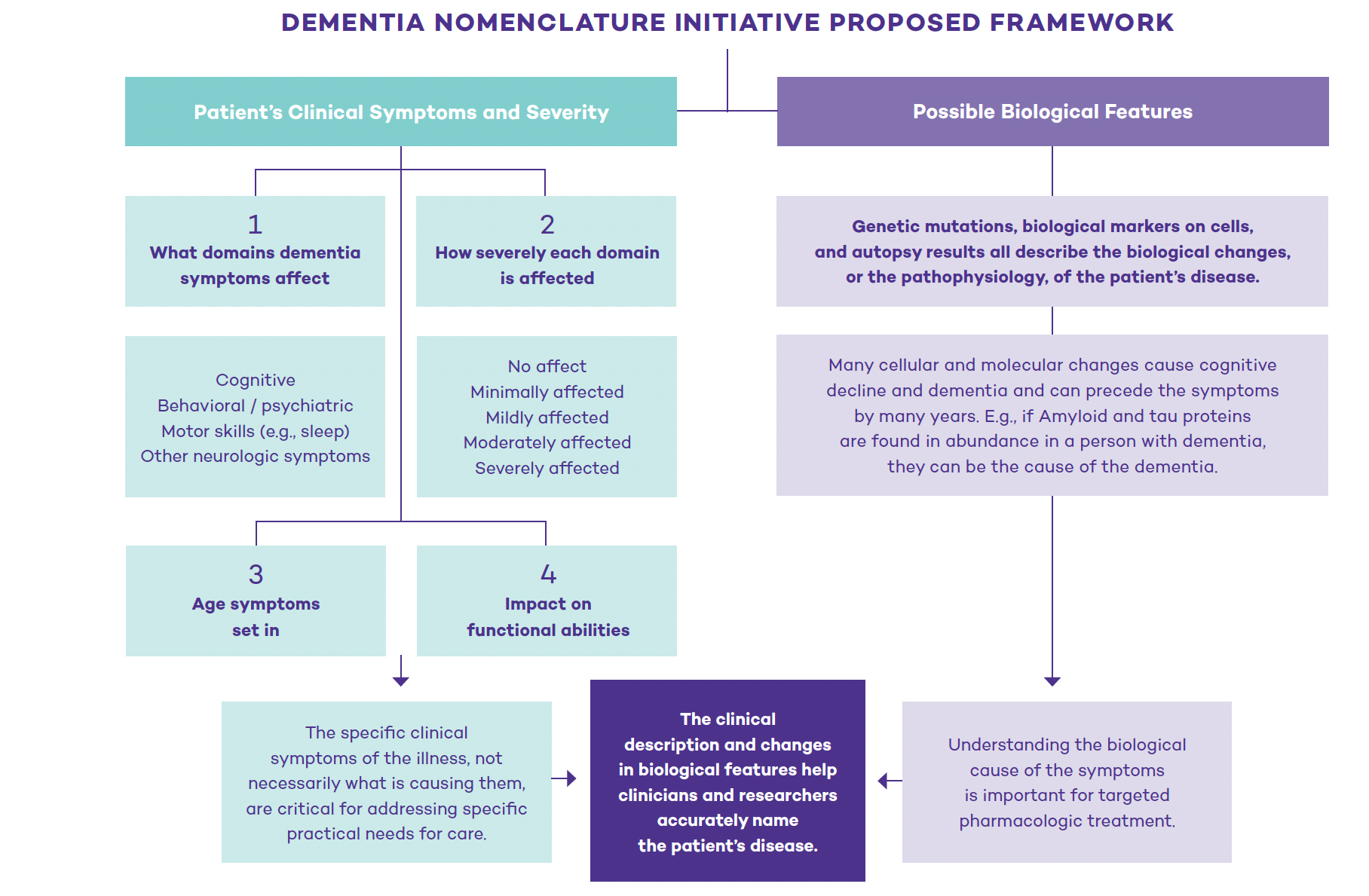

DeNomI published the first framework that differentiates between dementia’s clinical symptoms and biological changes that help identify the type of cognitive disease on October 16, 2023, through its initial study. The research team spoke to reporters about the importance of establishing a standardized naming system for researchers and physicians, which also helps educate the community on the differences between cognitive diseases.

Pictured are the Nomenclature Session panelists, Cara Fiernan Fallon, Sandra Weintraub, Mark Herthel, James Leverenz, Dominic Sisti, Jason Karlawish, Peggye Dilworth-Anderson, Cynthia Huling Hummel, Angela Taylor, Ronald Petersen, at the Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias Summit in 2019. (Image provided by Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias Summit)

Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD, co-chair of the DeNomI project and director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, realized that various cognitive diseases and terms associated with dementia were “used inconsistently” by patients, families, doctors and even the research community.

“It was clear that we were not all talking the same language, even though we were on the same committee,” Petersen said.

The team’s solution: designing a study to understand how patients, clinicians, and researchers describe cognitive diseases.

This included understanding where the miscommunication was happening, especially when differentiating between Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

“We’ve been doing a disservice to our patients by using terms loosely and inconsistently,” Petersen said. “I think it behooves us as clinicians to state how exactly we’re using the term Alzheimer’s disease.”

The initial study also helped the team prioritize racial and ethnic underrepresentation, since such exclusion has limited clinical care to majority White and upper-middle-class individuals, according to the publication.

Through the team’s initial focus groups, they found that in general there was more comfort around hearing disease labels than there was in hearing the term dementia, according to Taylor.

However, DeNomI isn’t trying to “fight” changing dementia nomenclature right now. The current push is to understand where existing names are coming from, according to Sandra Weintraub, PhD, DeNomI researcher and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Mesulam Center.

It boils down to understanding what words patients use to describe how the disease is expressing itself, which are the symptoms, and how patients describe the physical changes in their brains that are causing it, Weintraub said.

Understanding the differences between these categories led researchers to create a framework for future testing — one that separates the symptoms from the biology — according to Taylor.

“The public is now very educated on the difference between HIV versus AIDS and Coronavirus versus COVID-19,” Taylor said. “What we don’t have is an understanding between dementia and diseases that cause it.”

The Dementia Nomenclature Initiative published a framework on Oct. 16, 2023 to divide dementia-related diseases’ clinical symptoms and biology into two separate categories. Above is a flowchart illustrating how the two categories are set up. (Chart created by Ananya Chandhok)

“Passionately obsessed” with wanting people to understand the relationship between the two concepts, Weintraub remembered why she set out with this task force to begin with: to help her patients.

“He [my patient] would say, ‘You guys got to do this for me,’” said Weintraub when describing what a patient from the study said to her. “‘What’s wrong with me? Do I have a disease? Do I have a disorder?’”

The DeNomI team also realized it was critical to understand dementia descriptors across linguistic and cultural barriers.

“They [terms like dementia] are not only pejorative, but they mean different things in different languages,” Weintraub said. “If you say ‘you have dementia’ to somebody who speaks Spanish, you’re telling them they’re crazy.”

In the next phase, DeNomI plans on launching a pilot study to see how they can bring the framework into physicians’ offices, Weintraub said.

A key part of this process is recruiting ethnically and socioeconomically diverse communities and testing sites.

The pilot will use the established framework to do pre- and post-interviews in the next phase of the project.

The team hopes to gauge how well the framework works by evaluating how much patients, families, caregivers, and clinicians' understanding enhances after the post-interviews, Weintraub said.

“If we can increase the awareness of people’s use of these terms to ask ‘How am I using this term?’ Then getting people to just stop and introspect will be a success in itself,” Weintraub said.

Weintraub hopes that her team’s work helps patients, physicians and researchers to eliminate miscommunication and provide a foundation for equitable dementia-related healthcare.

“Why am I doing research if it’s not to help them?” Weintraub said.